Looking at silence in the arts in all its tightly wound forms.

Most synonyms of the word ‘silence’ speak of ‘calm’, ‘quiet’ or ‘noiselessness’. But these words don’t hint at the pent-up power of silence. Consider some of the ways we often talk about silence and its variants. We describe pauses as pregnant, with fitting responses ready to rip through them. The tension in a room after an outburst or disagreement can be palpable, something you can slice with a knife. This loaded version of silence even plays out in nature at times, when we experience the proverbial calm that comes before a storm.

The idea of silence as a precursor or corollary to something more violent or fierce is used very effectively in music. Classical music – both western and Indian – incorporates rests, along with notes, to balance out the composition, and to add both depth and tension.

In a 2009 Slate article, writer Jan Swafford uses examples to show ‘how a pause can be the most devastating effect used in music.’ The examples span the work of musicians from Handel to Beethoven who leveraged silence in incredibly powerful and unexpected ways. It was used as a lull before a soaring climax, a point from which to veer off in an unforeseen direction, or an abyss to fall into after hitting the tip of a crescendo. It is equally powerful in less operatic compositions. As a website on Jazz puts it:

“A few beats of silence can raise a listener’s expectation of what is about to come. Used in this manner, silence creates anticipation. [Silence] can release tension when it follows a phrase, but it also builds tension as the listener awaits the next phrase.”

It is this process of buildup and release that leaves a lasting impact on the listener. When asked whether there was one thing she could point to that made her music so divine, the doyenne of Carnatic music, MS Subbalakshmi, is said to have replied: “I think it is the silence between the notes.”

Many filmmakers have also used silence to great effect in their work. Tony Zhou, a San Francisco-based film enthusiast and freelance editor, has compiled a video montage, along with commentary, of Martin Scorsese’s ‘deliberate and powerful use of silence’ in his movies.

A boxing scene in the movie ‘Raging Bull’ with one pugilist getting ready to pummel his opponent plays out in highly charged silence before exploding in sound. In ‘Goodfellas’, a tense moment of silence between two gangsters after one of them delivers an expletive-filled speech, is defused when the other starts laughing.

In most cases, Zhou says, silence is used to highlight certain key moments of individual choice – to fight back, to take the money, and more. As it rolls, the audience holds its breath in anticipation of both that choice and its fallout.

Sholay, our own timeless masala western, uses silence sensitively in several freezes, most notably in the early scene when Thakur comes home to the slaughtered bodies of his family on the ground. There is restraint and eloquence in the quiet that follows after he lifts a sheet off of the body of his young grandson. The audience doesn’t see the body but can sense the spark of a rage that will soon consume the man.

Given that sound is integral to both music and movies, one can see how cutting it out can help to keep the listener or viewer on edge. But is that possible in a purely visual medium such as art? It can be if we think of silence in art as the act of withholding information.

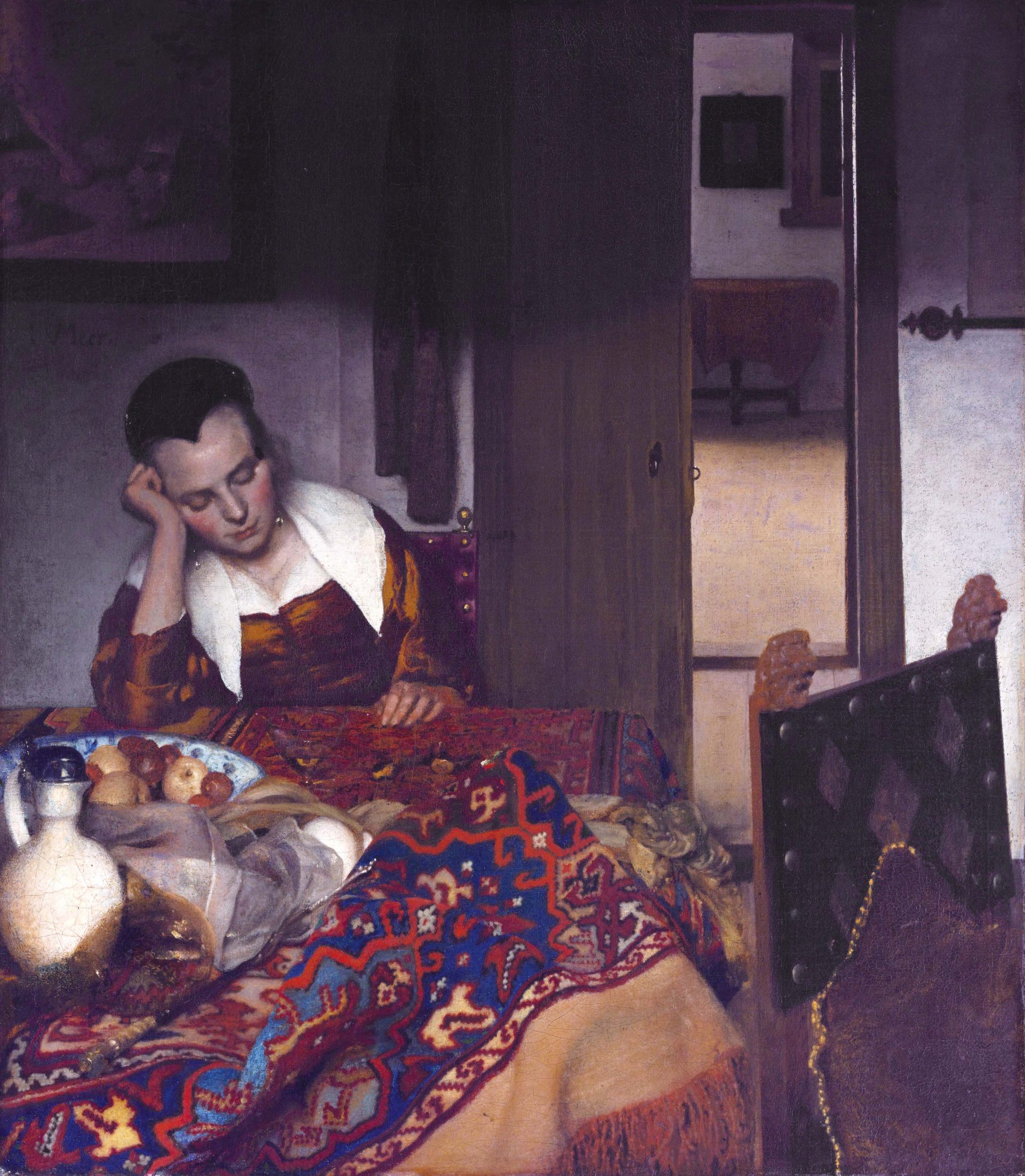

The Dutch master, Jan Vermeer, used this tactic in ‘Girl Asleep at a Table’, a painting that depicts a woman slumped behind a table, in an apparently inebriated state. Experts who have studied the work believe that Vermeer did initially have other elements in the frame, including a dog and a man who could be seen in the far room beyond the doorway. By editing them out, Vermeer left the scene and the state of its subject open to interpretation.

Vermeer knew, as does Scorsese, that silence is needed in the right doses to complete a frame. Not everything has to be spelt out, or every pause filled with sound. There is power and potential in the balance between silence and sound, between images and space.

But it can be a tricky balancing act, for filmmakers particularly. Zhou warns against cheapening silence by ‘overusing’ it or diluting its impact with background noise. Silence needs to be handled right for it to be completely felt. We can then revel in or reel from its after-effects.

References: Critical Assessments: A Maid Asleep. www.essentialvermeer.com